“As they say in poker, ‘If you’ve been in the game 30 minutes and you don’t know who the patsy is, you’re the patsy.‘” Warren Buffet, 1997

Marketing 101: Customers love free stuff. As a result, it is a common marketing practice to offer things “for free” in order to impact customer behavior or encourage customer loyalty. If you download their mobile app, Krispy Kreme will give you a free doughnut, McDonald’s will give you a free large fries, and Baskin-Robbins will give you a free scoop of ice cream. Believe it or not, the state of New Jersey has been experimenting with a free beer giveaway to encourage Covid vaccinations. It is cleverly promoted as a “Shot and a Beer.” Customers have shown again and again that they really love free stuff. That’s why it is a tried and true marketing scheme.

You know what customers like more than free stuff? You guessed it — straight up free money. A doughnut is one thing, cold-hard cash is even better. Paypal famously offered customers $5 to invite a friend, who would then also get $5 as part of a highly successful viral marketing campaign (they actually started at $20, and then reduced it to $10 and then ended at $5). According to an interview with Elon Musk, this campaign cost Paypal about $60 million, which most Silicon Valley historians would consider money well spent. Interestingly, many years later, Square would use other innovative “cash giveaway” strategies to steal market share from Paypal (in addition to copying the give $5, get $5 model). With Super Cash App Friday, customers who market and promote Cash App earn “entries” for a sweepstakes with an approximate retail value in weekly prizes of $20K. Instagram celebrities, or perhaps their wannabes, followed suit with their own version of Square’s sweepstakes, encouraging followers to promote the celebrity’s account as a way to have a chance at thousands of dollars.

While giving away $5 or perhaps a “chance” at $5K in a sweepstakes is somewhat interesting, what if I told you about a marketing program where each and every customer would get THOUSANDS of dollars, or TENS OF THOUSANDS, or HUNDREDS OF THOUSANDS, or maybe even MILLIONS of dollars, all in a single one day event? Do you think those customers would find that interesting and compelling? Would they be loyal? Would that help retention and NPS (Net Promote Score)? Damn straight it would. However, I know what you are thinking, “how would you ever fund such an endeavor?” It would cost a tremendous amount of money to run such a program. Billions of dollars.

This is where things get super interesting. What if I told you there was a way to get some external third party to naively fund all these giveaways, so it does not cost your company a single penny! Wouldn’t that be great? But hold on, it gets even better. What if I told you that you could systematically fool and exploit a whole class (hundreds and hundreds) of these external third-parties to fund these massive giveaway campaigns for decades and decades? And here is the cherry on top — what if you could convince them that funding your free cash giveaway marketing campaigns is in their own self interest? Sounds too good to be true?

On March 26, SoFi announced that “it will be offering its members (at least those with $3K in their account) the ability to invest in IPOs for companies going public, an investment opportunity that has traditionally been reserved for large institutional investors or ultra-high-net-worth individuals.” In this case “been reserved” is a euphemism for “limited to the best clients” of the investment bank. If somehow Sofi could obtain allocation to these so called “hot IPOs” clearly it would be a powerful marketing tool. After all, in the year 2020, investors that had access to VC-backed IPOs, earned $206 million in average one-day gains for each of 165 separate offerings, for a total of $34B in one-day wealth transfers (including over-allotments). Clearly, if Sofi could find a way to get cut in on this scheme, their customers would adore them for it. NPS would soar.

Not to be outdone, on May 20, Robinhood announced, “Today, we’re starting to roll out IPO Access, a new product that will give you the opportunity to buy shares of companies at their IPO price, before trading on public exchanges.” Like Sofi, Robinhood also noted “Most IPO shares typically go to institutions or wealthier investors,” highlighting the fact that obtaining access to these “hot”, one-day giveaways is indeed challenging. They also note that “IPO shares can be very limited, but all Robinhood customers get an equal shot at shares regardless of order size or account value.” This seems more like the Cash App Friday sweepstakes version of IPO access, but assuming Robinhood can get access, this should be quite successful. As already noted, free money giveaways are a proven marketing technique.

It is important to note that using the one-day gains of “hot IPOs” to either attract new customers or wildly please the ones you already have is not a new concept. On September 17, 1999, amidst the Internet IPO craze as well as the introduction of online trading (called GS.com herein), David Dechman sent an email to his colleagues in Equity Capital Markets at Goldman Sachs noting the following about “hot” IPOs (these are his exact words):

- The hot deals are obviously a currency, which can be used to please institutions, please high-net worth individuals, acquire new customers (perhaps for GS.com), help ECM as per the memo, etc. How should we allocate between the various Firm businesses to maximize value to GS?

- How much “say” do the issuers have? They have an obvious trade-off between a big “pop” (great media coverage and morale boost) versus more cash proceeds. Could we offer a “dial” to issuers and let them (and perhaps their ad agencies) decide? **

- For GS.com , EXCLUSIVE access to GS hot deal might be a critical competitive tool to keep customer acquisition costs low and encourage larger clients to more to our site from a competitor’s.

The main reason that the “Hot IPO” is such an obvious marketing tool is that transferring billions and billions of wealth to a prospective customer group is really, really, really effective. If $60 million can build Paypal, imagine what you can do with $34 billion in a single year! And as noted early, what if you could get some other naive third party patsy to be the one that funded the whole thing?

Putting “Hot IPOs” In Perspective

Regardless of whether it is run by Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Sofi, or Robinhood, the “Hot IPO” access marketing game has two key elements:

- Element 1: A method for systematically exploiting VC-backed companies by convincing them that selling shares in their company at a steep discount to the market price (where supply and demand would match) is in their own best interest.

- Element 2: Some process or program where you then transfer this wealth to your customers.

In the marketing announcements from SoFi and Robinhood, they focus entirely on element 2 of this system without mentioning that the entire program is dependent on the continued exploitation of these companies through intentional underpricing (Element 1). It doesn’t matter how they get access to the “hot shares” — the program is still 100% dependent on the company funding the free giveaway by agreeing to underpricing. If IPOs were priced “fairly” there would simply be no price “pop” to exploit or giveaway.

Make no mistake about it, an IPO “pop” is expressly a wealth transfer. Those that are allocated shares have definitive and explicit monetary gain within a 24 hour period of receiving an allocation. And this gain is one they can immediately take to the bank with no adverse legal consequence. There are absolutely zero restrictions against these accounts executing a “get rich quick, 1-day flip.” This “gain” ($34B last year alone) is a result of a direct wealth-transfer to these individuals FROM the previous owners of the company — founders, executives, employees, and venture investors.

These founders, executives, employees, and venture investors are unfortunately the “patsies” that have been funding the “hot IPO” marketing campaigns at investment banks for over 40 years. “Hot IPOs” are intentionally underpriced, and then the one-day gains are craftily handed to the very best customers of the investment banks. They return the favor by doing more banking business with said banks, and some of the windfall-money comes right back to the bank via other channels. Everyone in the industry knows IPO allocations are “hot” and “very limited.” And everyone knows who gets the hot shares — just like David Dechman laid out — the best clients of the investment bank.

Proof IPOs Are Intentionally Underpriced

Some may be startled at the strong assertion that IPOs are “intentionally” underpriced. Consider these facts:

- Start by poring over the data compiled by Jay Ritter at the University of Florida. Over 40 years, companies have funded over $200B in one day giveaways to the clients of the investment banks. Last year, 2020, the AVERAGE IPO was underpriced by 47.9%! If you add in 7% banker IPO fee, that represents a 55% cost of capital (for an entire year worth of IPOs, count 165). Jay has put together an exhaustive amount of data, and not once have I seen anyone use Jay’s data to take the opposite point of view. They all simply ignore it.

- IPO allocation is very difficult to obtain, is coveted by many, and is clearly perceived as a “benefit” in the Sofi and Robinhood marketing campaigns. How would all these things be true UNLESS IPOs were systematically underpriced? The desired allocation of the “hot IPO” is proof all by itself.

- On the demand side, the IPO process is limited to a handful of institutional investors and also ignores the vast majority of retail investors. Many, many more investors are locked-out of the process than are invited to participate.. This is exactly why Sofi and Robinhood marketing “getting access” is considered novel. Greatly limiting market participants is an intentional decision (and an unfair one).

- Investment banks simply do not match supply and demand. Electronic order matching systems that match all supply and demand for securities to determine a fair market price have been used in our financial markets since the early 1980s (approaching 40 years). The vast majority of all bond offerings are priced using the order matching system. And guess what, the day after your intentionally underpriced IPO, they then use an order matching system to start trading the shares on NYSE or Nasdaq the very next morning. Any bank that aimed to “fairly price” an offering would proactively use such an approach. It is actually easier and simpler (and exactly what is done in a Direct Listing/DL).

- When a company goes through a modern IPO process the bankers expressly tell the company that the “target” demand-supply ratio should be 30-50X oversubscribed. I kid you not —100% true. Their explicit goal is to ignore 97-98% of all demand (and this is “after and in addition to” heavily limiting who gets to put in an order!). It is absolutely ridiculous that this would be a target, and it is 100% tautological that such a process would result in MASSIVE underpricing. The banker’s even brag in marketing documents about this “achievement.” (see below). This is a “robbery in plain sight.” They are not trying to hide the evidence, they are promoting it! When I share this, reporters often ask me, “why is management so gullible to sit there and listen to a demand imbalance goal of 30x-50x?”

Are We Too Gullible or Naive?

Is it disrespectful to imply that the founders, executives, VC-backers, and the boards of these companies are gullible or naive? I don’t think so. I am a member of this group, and I have developed these perspectives over many years of watching from the inside and being equally gullible. Also, take a look at this critically important data point, also aggregated by Professor Jay Ritter. This data set looks at 8,610 IPOS over 39 years from 1980-2019. I want you to focus on the average first day return (over 39 years!) of VC-backed companies vs Buyout-backed companies. The average underpricing for all IPOs was 17.9%. The average VC-backed company was underpriced by 28.3%! (over 39 years, and this doesn’t include 2020 — one of the worst years ever). Here is the real gut-wrenching punch line. Over that same time frame, Buyout-backed companies were underpriced by only 9.2%. Thousands of companies over 39 years. We are the patsy.

It is important to restate and reflect on this one more time. Across 2,908 VC-backed IPOs the first day underpricing (euphemistically referred to as a “pop”) is 28.3%. With the 7% banker fee that is a 35% AVERAGE cost of capital. Over the same 39 year period, 1,137 buyout-backed IPOs had a 9.2% first-day “pop.” So for the past four decades, VC-backed companies have been exploited with 3X the underpricing of buyout-backed companies. That’s impossible to justify. When I share this shocking delta with others, the most common response is that buyout firms are simply more financially sophisticated and more willing to be aggressive and stand up for their interests. Large buyout firms are much more likely to have “capital markets” teams and much more likely to have experienced wall street executives in their ranks. On the flip side, it is very common to hear less sophisticated VCs/CEOs/CFOS/board members regurgitate the rhetoric from the investment banks about why funding their excessive marketing campaigns for their buy-side customers is in the company’s own best interest. It is long overdue to put an end to this exploitative practice.

Why Do We Let This Happen?

So, why are we gullible and why do we continue to allow ourselves to be exploited by this process? To help frame the discussion, let’s take a look at the three key parties in any IPO transaction:

- Party A: The company. The founders, the CEO, the CFO, the executives, the employees, and the venture investors. These are the parties on the cap table prior to the transaction.

- Party B: The investment banks. These are the third parties that are “running the transaction.” They are often called “underwriters” but this is a legacy term and is misleading. If you look up a definition of underwriting it involves “taking on financial risk” and “putting capital at risk” which they do not actually do in a typical IPO transaction.

- Party C: The buy-side investors. These are the institutions that are lucky enough to be considered for the limited allocation process. They also do business with Party B through their prime brokerage division and others. How much business Party C does with Party B directly impacts their eligibility for an allocation in “hot IPOs.”

1) Agency/Bias Issues With Respect to Advisors

Anytime you hire someone to represent you in a transaction you are subject to principle agent risk, the concern being you never know if the “agent” might be optimizing things for their own behalf, rather than simply working in the best interest of the client. As noted in the Wikipedia entry, this problem is exacerbated when subject to asymmetric information — when the agent has remarkably more data and experience than the client. As many founders and executives (Party A) will do only one, maybe two IPOs in their lifetime, there is massive asymmetry of experience in the traditional IPO. Both the members of Party B and Party C work on 30-40 IPOs per year. If they have worked in business for 20 years, you have an 700-1 experience differential right out of the gate.

That same Wikipedia entry has a note that is particularly relevant to the IPO process:

“The agency problem can be intensified when an agent acts on behalf of multiple principals (see multiple principal problem).When one agent acts on behalf of multiple principals, the multiple principals have to agree on the agent’s objectives, but face a collective action problem in governance, as individual principals may lobby the agent or otherwise act in their individual interests rather than in the collective interest of all principals.”

The traditional IPO is a very rare, super high-value (> $100mm) transaction where there is a single agent representing multiple parties in a the same exact transaction. When you conduct M&A, or even sell your house, everyone says you need your own representation. It is extremely rare to see situations exposed to multiple-principal risk, and it is fascinating that no one questions this in regards to the IPO process. Once again, including some super relevant detail on the subject from Wikipedia:

“Specifically, the multiple principal problem states that when one person or entity (the “agent“) is able to make decisions and / or take actions on behalf of, or that impact, multiple other entities: the “principals“, the existence of asymmetric information and self-interest and moral hazard among the parties can cause the agent’s behavior to differ substantially from what is in the joint principals’ interest, bringing large inefficiencies.“

If you were selling a company to Google, would you trust Google’s banker to give you advice at the same time? In that case, the normal and appropriate reaction is “that banker does way more business with Google than you, so they are going to do whatever Google says (inferring bias). You obviously cannot trust them.” So instead you hire your own representation to look after your own interest. For unknown reasons, our industry has ignored this obvious problem in the IPO process. Clearly Party B does way more business and much more frequently with Party C (Prime Brokerage) than it does with Party A. Also, as already discussed, there is a known 40 year history of underpricing IPOs. So we should naturally assume Party B is looking after Party C (just as David Dechman recommended)? It is logical that they would.

Despite this obvious direct financial bias to favor continuing with the “underpriced-IPO, free-money marketing game, members of Party A routinely seek advice from those in Party B or Party C when it comes to questions about how to go public. Silicon Valley founders and executives routinely say, “well the banker said we have to do this, or we can’t do that.” Remember, the bankers are the ones telling you it is “optimal” to have a 30-50X supply/demand imbalance on your IPO. Party A will also routinely ask members of Party C for IPO advice. Why would you ask for advice from the exact party receiving the incredibly large one-day, no-cost windfall? Interestingly, as more and more members of Party C move to compete in the late stage private market, they often pitch as “value-add” that they will help you navigate the public offering process because they have so much “experience.” But this “experience” is in collecting free single-day windfalls at the direct expense of the company. Why would you want advice from them? We should not be so easily manipulated.

Guess who is NOT invited to participate in the first-day IPO “pop” giveaway? Reflecting on Sofi and Robinhood’s desire to “cut-in” their customers on the underpricing exploitation, one is reminded of a time in the late 1990’s when the bankers in Party B did try to “cut-in” founders and CEOs (Party A) on the giveaway game (“hot IPO” shares). Known as “friends and family” (F&F) shares, in the late 1990’s, bankers would routinely offer IPO participation to the founders and executives around Silicon Valley, who were more than eager to have a chance, just like Party C has always had, for the meaningful one-day financial gains. In perhaps the ultimate irony, the press and the regulators all decided this was an unethical “conflict of interest” and that the practice should be immediately stopped. I am not saying there is NOT a conflict of interest with F&F, there clearly is. However, there is a larger and massive conflict of interest between Party B and Party C, as they routinely transact millions of dollars in other lines of business. And this conflict has been in place for over 40 years. The one party expressly prohibited from enjoying the “pop” is the one that actually funds the underpricing!

2) Rhetoric from Biased Parties

There is one drawback for Party A in interpreting the complexity of the public offering process. Party B, and frankly Party C, are really good at justifying why it should be in Party A’s best interest to keep funding this ridiculous game of single-day value transfers known as the IPO. They come up with all kinds of arguments like “don’t you want long-term shareholders” and “don’t you want to PICK your shareholders” and as Dechman suggested, “the IPO pop is great for marketing and employee morale!*” It is critical for members of Party A to look through this rhetoric and start looking after their own best interest.

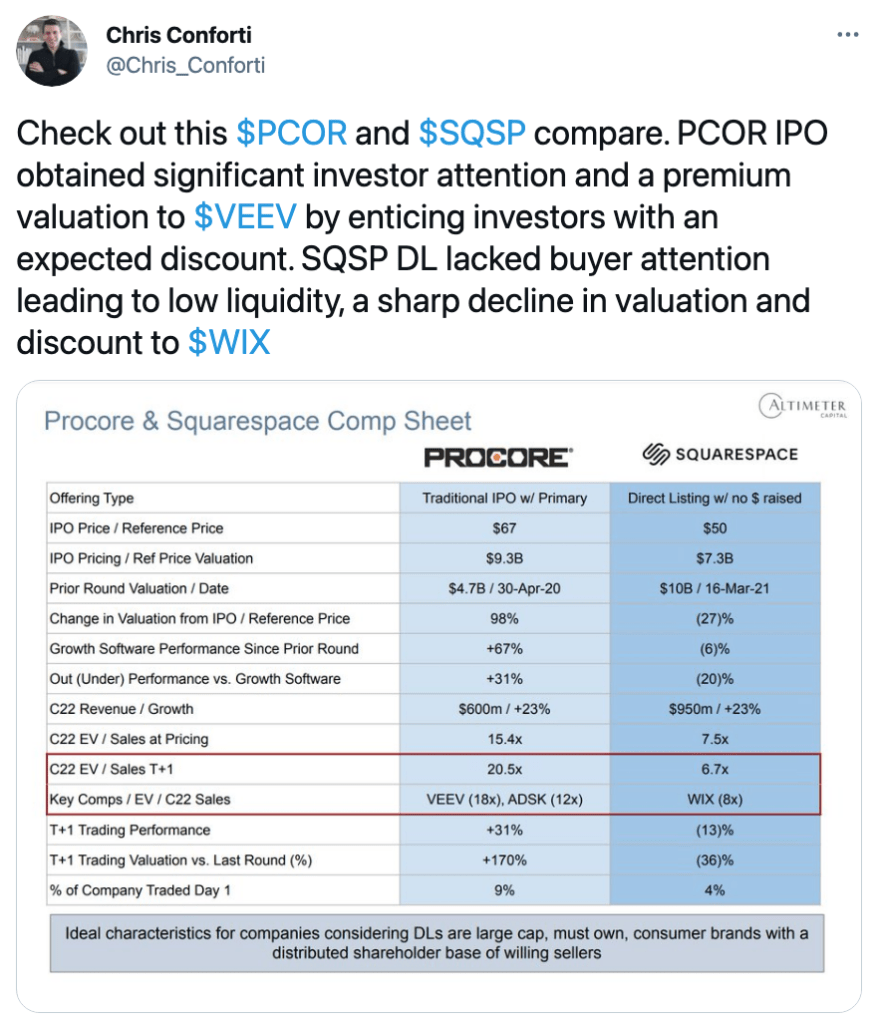

Here is a recent example of just such rhetoric, packaged as a tweet thread from Chris Conforti. Chris spent close to nine years working for Party B and recently switch over to a new firm in Party C. Despite this background and bias, he is quick to share his views to Party A on IPOs vs Direct Listing. The “tweet” in question is an analysis of a recent IPO (Procore) compared to a recent Direct Listing (Squarespace). You might flip over and read through it now, as well as the resulting thread, so that you have more perspective for the discussion. The primary argument Chris is making is that Procore ended up at a better relative valuation (from his perspective) to its peers than did Squarespace, and that the clear reason this happened was the choice of an IPO (his preferred decision) over a Direct Listing (which he implies is a bad choice).

The punchline of Chris’ argument is in the highlighted box, where he argues Procore is better off (having done an IPO and “as a result” of choosing the IPO), because Procore ended up with a valuation the day after the IPO of 20.5X forward 2022 sales which compares favorably with its top comparable $VEEV (which trades at 18X 2022 sales). He then argues Squarespace, as a result of choosing a Direct Listing, ended up with a valuation multiple of 6.7X, which he says compares unfavorably to its public peer $WIX (which has an 8X forward revenue multiple).

What I will now show you is that Chris’ analysis and arguments are entirely from the perspective of Party C, and are ignorant and tone-deaf to the interests of Party A:

- The 20.5X Procore multiple in the highlighted box, based on the first day close of $88 per share, is really the “Party C multiple.” Why? Party A is locked up at time T+1. They can’t sell the stock at this multiple and therefore that valuation is not available to them. Guess who can sell at $88 — the “Party C multiple” that Chris highlights? That’s right, Party C, the group that Party B allocated stock to the night before at $67. And that’s the only group that can.

- So if 20.5X is the “Party C multiple,” what is the “Party A multiple?” At first glance you would jump to the 15.4x number in the field right about the Party C multiple. Chris calls this the “at Pricing” multiple, and you should notice that is is much lower than the $VEEV multiple of 18X. Unfortunately, the real story is even worse. If the founder (or any member of Party A) participates in the IPO, they do NOT even receive the issue price. Why? Their proceeds are delivered net of the banker fee of 5-7%! So the true “Party A multiple,” adjusted for fees is actually 14.3X, 20% below that of $VEEV, and 30% below the Party C multiple in your own company shares. As a side note, the single individual most likely to transact on the sell-side of the IPO is the founder. If you read S-1’s frequently you will see that this is true. So the founder if the one most penalized by this broken process.

- Guess who else experiences the 14.3x “Party A multiple?” The actual company that is selling shares. Remember the whole point of this “offering” is to facilitate a transaction for the company. “The company” chose the path to the public markets. Yet, the company is getting the worse deal of all. Procore sold 10.4 shares of stock in IPO and received $661mm dollars (assuming a 5% banker fee). On day T+1, those same exact shares were worth $915.2mm (this is the Party C multiple Chris raves about) and are freely tradable (even though they have held them for less than 24 hours). In one day, the lucky members of Party C that were handed stock by Party B had an instant free gift of $254mm. Where did this money come from? It came right out of the pockets of the members of Party A.

- Now let’s turn to the Squarespace example. In this case, the “negative” data point in Chris’ analysis (highlighted box) is the multiple of 6.7X, which represented the closing price of the Squarespace stock on the first day of trading. This multiple would only matter for those that received shares in the Direct Listing (as a result of an order matching system allocating shares to the highest bidders) that want to immediately dump their stock (as they sometimes do with an IPO). We should call this the “Party C Flippers” multiple. I can only infer he also thinks this is the constituency for which you should optimize your offering choice. Personally, I think the Party C one-day flipper should have no consideration whatsoever.

- Interestingly, the 7.5X multiple that he leaves out of his highlighted box, is the actual multiple received by the members of Party A that sold into the transaction (founders, employees, and investors). Today’s DLs do not include primary capital and so the company did not transact at this price. That said, the NYSE and NASDAQ have SEC approval for “Direct Listing with a Primary Raise.” In that case, the company would also have used this 7.5X multiple. So with the DL, Party A transacted at 7.5X, which represents 94% of the comparable peer chosen by Chris ($WIX in this case). And, unlike the IPO, the banker fee is not borne by the sellers. With Procore’s IPO, Party A transacted at 79% of the comparable $VEEV multiple. Party A (company, founders, employees, investors) are clearly WAY BETTER off with the Direct Listing. And once again, they are the ones deciding on the approach to the public markets.

Here are some other nuggets Chris uses on Twitter to mislead founders into believing an underpriced IPO is in their own best interest:

- On April 21, 2021, Chris tweeted that “$PATH and $DV IPOs hit the rare IPO pop bullseyes (+15% – 30%). Great to see.” Great for who? Party C, that is who. Why is a 20-30% cost-of-capital (including fees) in an ultra low-interest rate environment a “sweet spot”? It is unquestionably an “awesome free-stuff” outcome for Party C. But that is a horrific target cost-of-capital for any institution raising capital.

- Why does Chris think all of us in Party C should be “happy” with consistent underpricing? On May 22,2021 he surreally tweeted, “In a volatile market, investors need an incentive to do the work – the expectation of an IPO pop.” I had to read this three different times, just to make sure I read it correctly. This is perhaps the most ignorant, disrespectful, and entitled comment I have ever read about the IPO process. When did things get so wonderful on the buy-side, that you cannot afford to ask an analyst in your shop to even pick up a pencil unless there is a guarantee of a free $200mm+ available? Why would a founder or CEO want an investor on the cap table who was only interested in “paying attention” to the company if there is a large, free, one-day incentive? You should aim to avoid investors with this mindset.

- At the bottom of Chris’ comp sheet, he throws in more dart attacks at Direct Listings, with no justification or support. He says “Ideal characteristics for companies considering DLs are large cap, must own, consumer brands…” I believe strongly that once we have DL+Primary, every single company should chose the DL path — order matching is modern, elegant, and unarguably better than hand-allocation. Yet the members of Party B and C that want to keep the “free stuff” marketing game going want you to believe that DLs are “just for certain companies.” This is simply wrong.

- Look at the following table recently posted on Twitter by Ari Levy, summarizing the DLs of the past 2 years or so. As a group they have done quite well. Of the eight, only three (Spotify, Roblox, and Coinbase) are consumer focused companies. The others are all B2B companies. So the majority of companies with successful Direct Listings are NOT consumer. This is opposite of what Chris proclaimed.

- Why would a DL need to be a “large” company? This is a statement with nothing to back it up at all. Order-matching systems are used in bond offerings of all sizes, not “just the large ones.” A DL would do just fine with a smaller offering.

- He also says they need to be “must own” names. Once again, this is demonstrably wrong. Are Asana, Palantir, ZipRecruiter, and Squarespace “must own” names? Any company can chose to Direct List. Most people do not know this, primarily because of rhetoric just like this, but there are actually more opportunities to market your company with the Direct Listing (as compared to the IPO). The IPO marketing process consists entirely of 1-1 meetings. With the DL, you do an entire online investor day and ALSO can chose to do the 1-1 meetings. The DL marketing opportunity is a super-set of that you have with an IPO, and therefore better for the lesser known company.

One hilarious part of this story is that had Chris simply waited one week he might have never written this post. Why? On their fifth day of trading, Procore shares traded down from $88.0 to $81.5, probably a result of the lucky Party C flippers cashing in on their one-day freebie gains. And guess what? After falling from their DL match price of $48 all the way down to a first day close of $43, Squarespace shares climbed all the way up to $55.

What if, instead of spending all this time trying to discourage future founders away from a DL and trying to preserve the one-day “pop” giveaway, Chris had actually done security analysis? Let us assume that Chris truly believes that Direct Listings result in an “inferior” close-of-first-day trading price. That is after all, the whole punch line of his post. Rather than posting on Twitter, he could have been buying the mis-priced $SQSP stock for his firm. If he had done this, he would have done very well. One would think this is the exact type of “incentive to do the work” that makes buy-side firms tick. But perhaps it is just easier to write Twitter posts that argue for the entitled one-day marketing giveaways.

3) Leading Us to a Better Future Requires Courage

Bill Hambrecht was a co-founder Hambrecht and Quist in 1968. Hambrecht and Quist (based in San Francisco) which was one of four investment banks that catered to the entrepreneurs and VC-backed companies through the late 1990’s. These banks were affectionately known as the Four Horsemen, although the large Wall Street banks referred to them with the derogatory acronym of HARM. Because of the geographic proximity, as well as their sector focus, these banks were more attuned to the special needs and concerns of our ecosystem. It is with this backdrop that Bill Hambrecht, with decades under his belt in investment banking, declared “IPOs have always been handled by traditional investment banks, and essentially it’s sort of an insider’s game – goes back 120 years, really.” Bill, through the use of the Dutch Auction, attempted to right the two key wrongs of the standard IPO. Hambrecht stated, “I felt it was a lot fairer to open up the market to every investor. And number two, do it at a market price.” Bill saw then the problems we are still facing today. But we are getting much, much closer to a solution.

In a 2019 article in the Financial Times titled, “Investment banks are losing their grip on IPOs,” Sequoia Capital’s Mike Mortiz argues, “the choice of a direct listing or a traditional IPO has become a test of two attributes: courage and intelligence.” When you look at the ridiculous 40 year history of underpricing, and fully understand the “moronic” process used to engineer underpriced IPOs, it is easy to understand why the Direct Listing is the far more intelligent choice. Smart founders and CEOs understand this clearly. That said, the “courage” issue is real. Fighting the massive amount of persuasion and rhetoric that comes from the members of Party B and Party C is difficult. Also, as many founders and CEOs only go public once, it is much easier to take the traditional conservative route, vs doing something innovative and courageous.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/59230987/932524604.jpg.0.jpg?resize=279%2C186&ssl=1)

It took courage for Bill Hambrecht to stand up to the Wall Street establishment. It took courage for Larry Page and Sergey Brin to push for a Dutch Auction at Google. It took courage for Zach Nelson and the team at Netsuite to also use a Dutch Auction in 2007. It took courage and immense determination for Barry McCarthy (with the help of Daniel Ek) to push through the first modern Direct Listing. After Daniel and Barry came Stewart Butterflied at Slack, Alex Karp at Palantir, Dustin Moskovitz at Asana, David Baszucki at Roblox, Brian Armstrong at Coinbase, Anthony Casalena at Squarespace, and Ian Siegel at ZipRecruiter. Two other courageous individuals are Stacey Cunningham, the President of the NYSE and Adena Friedman, the President and CEO at NASDAQ. Both Stacey and Adena have been working hard with regulators to help push forward to a more modern future. Lastly, Greg Rogers at Latham has been there for every step along the way. If you need DL legal advice, call Greg.

Spotify needed a full two years to affect their Direct Listing. As a result of their pioneering work, and the path clearing work of these many other founders and CEOs, you can now get a Direct Listing done in the same time as an IPO (about 6-7 months). And as soon as the next courageous pioneer pushes through a Direct Listing with a primary raise, we will be further along the path to everyone going public with the use of an order matching system and the elimination of IPOs that are limited to only a select few bidders. So each and every courageous founder that goes through this door makes it easier for the next one to follow.

Moving on to a More Elegant and Fair Approach: The Direct Listing

Never lose focus of the two key reasons the Direct Listing is vastly superior to the IPO. And do not be dissuaded by the rhetoric that comes from those trying to preserve the status quo and free-money train. These two critical differences are the exact same two Bill Hambrecht was pushing on over 20 years ago.

Two Key Direct Listing Differences/Advantages

- The Direct Listing uses an order matching systems to allow supply and demand to determine both price and allocation and to find the true market price. The order book is “blind” — meaning every shareholder is treated the same, and no bidder gets any advantage based on their status, name, or customer influence within a bank. If you bid $0.01 above the closing price, you are filled, even if you submitted your order through Schwab, E-Trade, or yes even Robinhood.

- The Direct Listing is open to any and all investors with any brokerage account connected to the exchange. As Robinhood attempts to squeeze their way into the broken IPO process, this is not “democratizing the IPO” as they claim. It only “cuts in” Robinhood customers, and leaves everyone else (Schwab, Etrade, etc) outside. The DL truly democratizes the public offering process by inviting in EVERYONE. No one is excluded.

When you have a discussion with any DL naysayer or skeptic — force them to address these two questions (which they will try avoid at all costs). They will resist, because they know both these approaches are clearly more legitimate that what happens with the IPO today.

- Why would you NOT use supply and demand to determine price and allocation (the true market price)?

- Why wouldn’t you open public offerings to all interested parties (and instead restrict access to a limited number of extremely wealthy/elite participants)?

For those considering a public offering, look back once more at the list of eight successful Direct Listings companies from the past few years. Not one of these companies played the role of “patsy” for someone else’s marketing game, at not one of them paid the $200mm “IPO Pop Tax” that the average company that went IPO in 2020 paid. All of them used a modern order matching system open to all shareholders to find the true market price. Once you go public, no one keeps track of how you went out. Everything is about how you execute going forward. There is no DL-sticker on the company’s ticker, and even if there were, it would simply signal a very high-judgement CEO that understands fiduciary duty.

Thanks to the pioneering work of Barry McCarty and others, paying the “IPO Pop Tax” is now 100% optional.

We are on the verge of knocking down a wall; of righting a wrong; of ending an exploitive process where we are undoubtedly the “butt of the joke.” Hambrecht, Page & Brin, Nelson, McCarthy & Ek, Butterfield, Karp, Moskovitz, Baszucki, Armstrong, Casalena, Siegel, and many others have blazed a trail. And the more companies that push through this brave new trail, the easier the path is for each company coming through. Let’s keep pushing. We are getting closer and closer to ending this remarkably unfair and broken process.

** I have never seen an investment bank offer a “pop” dial to a company’s ad agency, but if you want to boost company morale I suggest giving cash directly to your employees versus using that cash to fund a marketing giveaway for brokerage clients.

You must be logged in to post a comment.